Forces Engaged: British Imperial

Five battalions of infantry: one, the 2nd Bn The Derbyshire Regiment of 1st Brigade, First Division, one, the 3rd Regiment Sikh Infantry (Punjab Field Force) of 2nd Brigade, First Division, and three; 1st Bn The Dorsetshire Regiment, 1st Bn, 2nd Gurkha Rifle Regiment, and 1st Bn Gordon Highlanders from 3rd Brigade, Second Division.

Each battalion probably at or near full strength of ten companies of 70 for a total of roughly 3,500 infantrymen.

Four batteries of mountain howitzers (No. 8 and No. 9 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery, No. 1 (Kohat) Mountain Battery and No. 5 (Bombay) Mountain Battery) firing RML 2.5" Mountain Guns (often referred to by the British troops as "Screw Guns") I have had a difficult time establishing the MTO&E for these units. A typical battery appears to have six cannon, and each cannon appears to have had a crew of between six and eight; note the photograph below:

But the battery itself must have had at least another half-dozen or so troopers acting as ammunition numbers, extra crewmen, odds-and-sods, as well as at least a battery sergeant-major and an officer. So probably about 50-70 redlegs per battery for a force of 24 cannons and 200-250 artillerymen,

At least one source reports the presence of a machinegun detachment but does not identify the unit as such. By 1897 British (that is, Imperial) infantry battalions carried an MG detachment of 2 x 0.45 calibre Maxim machinegun and 20 troops on strength. However, in the order of battle for the Tirah Expedition among the Divisional Troops for Second Division is list a "Maxim Detachment, 16th Lancers", so this may have been the machinegun unit present at Dargai.

So roughly 3,500 infantry, 250 artillerymen, 24 cannon and two machineguns. The commander on the scene was MG A. G. Yeatman-Biggs, Second Division commander; the entire Tirah Expedition force was commanded by MG Sir William Lockhart, GCB KCSI, and isn't he a wonderful picture of late Victorian generality;

Orakzai (اورکزی) and Afridi (اپريدي) Tribal Forces

An undetermined number of Afghan tribal warriors drawn from the two tribes then fighting the British Indian forces. The most likely composition of the defending forces, however, was from one or more of the Orakzai clans, since that tribe then controlled the high ground in the Tirah area. Several sources mention Afridis, and Afghans being Afghans it's hard to believe that with killing in the offing that the eager young men of the tribe could have been held back.

The numbers of defenders are usually simply described as "hundreds" to "thousands". The British attackers, who ended up in control of the Heights, probably had no real idea how many Afghans they were fighting; the tribesmen, no fools they, ran off when it became obvious that the mad invaders weren't going to stop coming on.

But there must have been at least several hundred; anything less than that wouldn't have been able to produce a sufficient volume of fire to have had the effects as described on the attackers.

While as many as 10-12,000 fighters manned the crest of the heights altogether the area of the British assault appears to be a fairly small area - indeed, a single narrow path; more an a couple of thousand guys would have been tumbling out of their sangars like ripe fruit off a plum tree; the British wouldn't have been able to leave their start line without being riddled like Swiss cheese.

So the force actively defending the path up the heights on 20 OCT probably numbered somewhere between 1,000 and 2,500. We have no idea who the "commanders" were; in typical tribal fashion the guys probably coalesced in lashkars around a local hardcase, a religious leader, or a cunning planner in little knots of five to fifty.

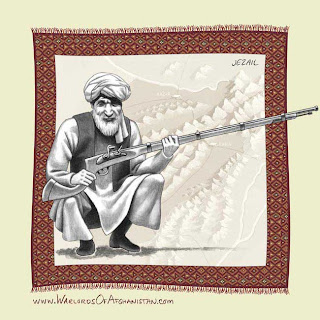

A Note On Armaments: At Dargai the British and Indian troopers were armed with issue rifles; the British with the relatively new .303 Lee-Metford bolt action rifle (shown above), the Indian troops with the older Martini-Henry lever-action breechloader.

Many of the Afghans must have been armed with the traditional jezail, the long rifled musket of the high hills around the Durand Line. But one of the nastiest shocks of Dargai, and the Tirah campaign as a whole, was the presence on the battlefield of modern rifles in Afghan hands.

The combination of the Afghan hillman and the modern rifle was a deadly natural. The British found that wog-bashing in 1897 wasn't nearly as much fun as it had been earlier now that the bashees had their hands on modern weaponry.

After the Tirah Expedition concluded the surprise and displeasure at the lack of fun to be had in the Kurrum Valley is evident in the plaintive tone of Queen Victoria's letter to her Viceroy of India: "As we did not wish to retain any part of the country, is the continuation and indefinite prolongation of these punitive expeditions really justifiable at the cost of many valuable lives?"

Sadly, this simple lesson had to be relearned over and over again.

The Sources: Military actions taken by literate industrial nations tend to be well documented, and Dargai is no exception. Written accounts of the actions of the Tirah Expedition and its Afghan opponents appeared almost before the rigor passed off the dead guys; one of the most complete is found here: The Campaign In Tirah 1897-1898 An Account Of The Expedition Against The Orakzais And Afridis Under General Sir William Lockhart, G.C.B., K.C.S.I. based (by permission) on letters contributed to "The Times", written by one COL H. D. Hutchinson in 1898.

Other contemporary British sources include The Indian frontier war being an account of the Mohmund and Tirah expeditions, 1897 (James, L. 1898) and Lockhart's Advance Through Tirah (Shadwell, L.J. 1898)

Secondary accounts include The 1897 Revolt and Tirah Valley Operations from the Pashtun Perspective (Johnson R.A. 2009), an invaluable view from the "other side of the hill", unusual in colonial war, and Michael Barthorp's 1996 The Frontier Ablaze: The North-West Frontier Rising, 1897-98.

Byron Farwell's 1985 Queen Victoria's Little Wars tells the old savage-and-soldier tales with gusto, while perhaps the most entertaining version of the engagement is told in George McDonald Fraser's little story "The Whisky and the Music" told in The General Danced At Dawn, his volume of tales about his times in the Gordons.

More of that later. First, the fighting.

The Campaign: I can't really do a better job of explaining why 60-some thousand British and Indian troops set off into the highlands around the Khyber Pass in the autumn of 1897 that Rob Johnson can, so, here:

"The largest and most serious outbreak of fighting on the North West Frontier during the colonial era was the Pathan Uprising of 1897-8. The revolt was actually a series of local insurrections involving over 200,000 fighters, including Afghan volunteers, and it required over 59,000 regular troops and 4,000 Imperial Service Troops to deal with it; the largest deployment in India since the Mutiny-Rebellion of 1857-8. Its outbreak proved such an unexpected and significant shock to the British that they conducted detailed enquiries after the event.

Various explanations were offered but it is generally accepted that recent encroachments into tribal territory, with fears that the British meant to permanently occupy the region as a prelude to the destruction of their independence and way of life, led to the initial fighting. There were other contributory factors: a perception that the Amir of Afghanistan, Abdur Rahman Khan, would support an anti-British Jihad; rumours that the Christian Greeks had been defeated by the Muslim Turks and that the Christian world was finally in retreat, and local anxieties about women, money-lenders and road-building."But the money was always on the British and the Afghans to fight. They both loved to fight, and they both wanted the other to get the fuck out of their crib. I used Farwell's book to dredge up a list of Afghan Wars for this post over at MilPub back in March of last year. Turns out that there was about one "expedition" or "column" or "punitive action" or "field force" every year or so beginning in the 1830s and running well into the 20th Century; the Third Afghan War was fought in 1919!

So while this was a big one, it was not a new one, or even a really surprising one other than it's size.

The actual fighting of the 1897 "rising" began on 10 JUN, with an ambush of a smal force near Maizar. During this engagement something occurred of the sort of ridiculous criticality that distinguished truth from fiction; fiction would never be this incredible. I'll let Johnson (2009) describe it again:

"The British artillery soon ran out of ammunition in the engagement and was forced to use blank rounds in the hope that this would deter a pursuit. Ironically, this fulfilled a prediction by the more enthusiastic mullahs: they had assured the tribesmen that the British shells would turn to stone and their bullets would turn to water the moment they hit the breast of a true believer. They demanded a Jihad to save the religion and condemned those they appeared to be profiting by association with infidels."

The rising exploded, and in August all the forts along the Khyber Pass fell, lending immense prestige, as well as lots of modern weapons and ammunition, to the Afridi tribesmen who pulled off that raid. Many of the Orakzai and Afridi clans rushed to join up, either with view of a full-scale victory over the infidels or just hopes of a bit of plunder on the side.

But it's important to see that the tribes weren't just mooks looking for loot. There was an actual plan. The Afridis wanted to push the Brits out of the Khyber Pass and Tirah Valley region, while the Orakzais wanted to drive the British off the Samana Ridge that was the key to their territory.The Khyber plan worked, but the attacks on Samana weren't as successful. One fort, at Sarigari, did fall, but British reinforcements and, as or more importantly, their artillery held the Samana.

The tribes also hoped for support from Kabul, but the Amir Rahman Khan, while offering some rousing anti-British orations to the tribal delegations, did nothing but talk.

His tepid response was designed to prevent looking like a foreign stooge (always dangerous for an Afghan ruler) while finding a pretext for doing nothing. Eventually he "...admonished the tribesmen and ordered them to settle their differences with the British, claiming he had made agreements he could not break...(and that) the tribes had not informed him of their intentions

before the outbreak of violence." (Johnson, 2009)

Although the Amir refused active support he did not prevent the tribes from using eastern Afghanistan to maneuver in and retreat to.

While the Afghan troopers knew the Brits would come at them - they always had before - the real question was how. The Khyber Pass was a high-prestige target and would undoubtedly be attacked, but how would the British approach the home territories of the tribes in arms?

They could attack due west from Kohat along the Khanki Valley.

Or they could strike north up the Mastura River from Peshawar.

But there was another problem; the late summer was upon them, and men had to go home to bring in the harvest. Crops wouldn't wait for the damn Brits. Many of the Afghans left...and for two months the British didn't come.

What the Afghans couldn't know is that the British WERE on their way but were having the devil's own time with logistics. To carry the bag and baggage the British concluded they'd need a baggage animal for every six white troops, every eight native troopers, and every ten camp-followers; something like 20,000 horses and mules and 15,000 camels. Shadwell (1898) has some delightful details on the allocation of pack animals to the force on pages 113 and 114; general officers got a pack mule and a pony, in case you were wondering.

But finally the first Indian pioneers - what we'd call combat engineers - turned up near the Shinwari fort south of the Samana Ridge in October gave the game away; the British were coming, horse, foot and artillery.

At this the tribes convened a jirga in the cillage of Bagh where the leading lights roared for war and jihad against the infidel. That didn't stop a mob from the Orakzai out of Kanki Valley to try and surrender to MG Yeatman Biggs. The general told them that he couldn't take their submission while their buddies were still out looting and raping, so (presumably with heavy hearts) that went back to join the revolt.

The road up from Samana Ridge was overlooked by high ground to the north; the Dargai Heights.

Johnson (2009) quotes "one British officer" (in this case, Callwell 1911) saying that "the natural defile at Dargai not only made a defensive stance far easier, it also afforded ‘excellent cover, naturally provided by the rocks and improved by walls, etc, built up by [the tribesmen]’. Shadwell (1898) gives an even more vivid description:

"The village of Dargai lies on the northern side of a small plateau. The eastern edge of this table-land breaks off, at first, in an almost abrupt cliff...but...lower down...shelves away less precipitously. This slope is thrown out from the bottom of the cliff in the form of a narrow and razor-like spur, with the path or track lying along its northern side, well within...range of the cliff-head."The picture from Shadwell's book is shown below.

He describes the photo above, noting that "The narrow ridge at the right-hand bottom corner is the saddle over which the rush had to be made on the 18th and 20th..."

Connecting the crest of the spur...and the foot of the cliff there is a narrow neck or saddle one hundred yards long by thirty broad...devoid of all cover and completely exposed to the heights above, this ridge had to be crossed to reach the path ascending to the summit..."

On 18 OCT a force from the Second Division assaulted the heights; the movements of the British troops are in blue on the map above.

The 4th Brigade attacked from the village of Chagru Kotal while the 3rd Brigade swung around to the west. Afghan resistance was light, and the attackers easily took the crest of the ridge, the Afghan defenders falling back before them.

At this time GEN Lockhart made what has to be considered a mistake; he withdrew the force from the heights. In his tame reporter's letter to the London Times he says that the force was too isolated and unsupportable as well as difficult to supply.

All of that may have been true. We have no idea what would have happened if the British had tried to hold the heights.

But the problems that would come of the decision to withdraw were immediate and should have been evident before the last soldier came down off the hills.

The firing of the day's engagement had drawn a crowd; Shadwell (1898) says about 8,000 mixed Afridis and Orakzais were arriving from the nearby Khanki Valley as well as the original defenders of Dargai village returning to snipe at the invaders.

On the way downhill the British force suffered worse than in the attack from this converging force; finally dark and the artillery halted the Afghan pursuit but the Second Division lost 10 dead and 53 wounded in the operation for no tangible gain.

And, then, worse.

Late the following day (19 OCT) MG Yeatman-Biggs sent his commander a telegram from his position at Shinawari. He reported a "large gathering of tribesmen was visible on the Dargai position, and...proposed moving on Karappa, via Gulistan Fort, instead of down the Chagru defile." (Shadwell, 1898).

This move would have effectively turned the Dargai position, but GEN Lockhart "ordered the original route to be adhered to, remarking that, while it would probably be necessary to clear the enemy off the Dargai heights, they would very likely retire, to prevent their line of retreat from being threatened..." (Shadwell, 1898)

MG Yeatman-Biggs shook out his force to recapture the heights of Dargai.

The Engagement: Note - There are several sources for the attack on 20 OCT but the following account is primarily from Shadwell (1898) supplemented by Johnson (2009) for observations from the Afghan side.

The British attack force was organized in three waves. The first unit to assault was the 1/2 Gurkhas, the second "wave" was the Dorsets, with the Derbyshire Regiment third. The Gordons were originally tasked with supporting fire.The defense was spread all along the crest and military crest of the Dargai ridge. Shadwell (1898) notes that the defenders didn't make the same mistake as on 18 OCT; the defensive perimeter extended well to the west, where MG Kempster's flanking attack had climbed the cliffs. In the Shadwell account this is supposed to have been due to a cunning ploy by the Second Division intel officer - or "political officer" as they were called at the time - who fed the tribes a false plan, but there is no way to be sure that this was not merely a tactical adjustment to the British attack of the 18th.

Artillery prep began at 1000 hours. The Gurkha attack went forward soon after - Shadwell (1898) is not specific about the time, and the assault appears to have been effectively halted by fire along the saddle or at the base of the steep cliff within a short time of leaving the line of departure.

"Many a brave little Ghoorka bit the dust" is how Shadwell puts it.

Really. No shit. That's what he wrote.

Apparently some time soon after the two British units attempted to reinforce the Gurkha battalion. Both were shot to pieces as they tried to rush the saddle. Most of the British troops were killed in the open space. Neither unit, nor the Gurkha Rifles, could manage to advance up the steep path to the crest.

Johnson (2009) describes it thusly: "As they tried to cross in small groups ‘each clump of men that dashed forward melted away under the converging and accurate fire, and after a time affairs practically came to standstill’. The Gurkhas were pinned down for three hours and 2 other British regiments fared little better."

At some time in the early afternoon - probably about 1500 - BG Kempster was tasked to bring up the division reserves; the Gordons and the 3rd Sikhs. These units were "shot across" the open saddle by an artillery mad minute in which all 24 cannons fired a three-minute rapid fire.

The Gordons and Sikhs managed to make the base of the cliff in a body, probably picking up odd lots of Gurkhas and British soldiers along the way. From there it must have been a mad scramble up the steep path into a nasty rain of rifle fire.

One of the Gordons pipers, a man named Findlater, was shot through both legs at the ankles on the way up. He hauled himself onto a rock and continued playing as his fellow tribesmen attacked. His was the sort of bizarre gallantry that transfixed Victorian audiences; he got a sort of nursery rhyme from the kiddies of Glasgow out of it:

"Piper Findlater, Piper Findlater,

Piped "The Cock 'o the North".

He piped it so loud,

He gathered a crowd,

And won the Victoria Cross."

And so he did, although just to remind us that life isn't like the stories we like to tell about it, he later remarked;

"I am told that the ‘Cock of the North’ was the tune ordered to be played, but I didn’t hear the order, and using my own judgment I thought that the charge would be better led by a quick strathspey, so I struck up ‘The Haughs o’ Cromdale’. The ‘Cock o’ the North’ is more of a march tune and the effort we had to make was a rush and a charge."Ha! Take that, popular fiction...

The final rush carried the crest, again the Afghan defenders retired in good order, and the 1/2 Gurkhas and Dorsetshire Regiment were posted to hold the crest while the rest of the attack force sloped off back down to the valley below to police up the dead and wounded and reorganize for the move forward.

A total of 37 attacking infantrymen were killed, with the point element suffering the worst; 1/2 Gurkhas lost 18 officers and men. Another 156 British troops were wounded. The Afghan losses were not counted, but the defenders managed to remove all their dead and wounded before the attack force seized its objective. "Many bloodstains were found on the ground..." is all Shadwell (1898) can come up with, remarking that the women and children commonly dragged off both wounded and killed.

Johnson (2009) sums up the Afghan tactical moves and their effects:

"First, and most importantly, the new Pashtun deployments had compelled Lockhart to change his plan to by-pass Dargai. Second, the tribesmen carefully selected (the ground) and channelled them into a specific killing area. Almost all the British casualties occurred in a one small area that could be swept by small arms’ fire. The British had suffered 200 casualties, and, whilst the tribesmen were forced to abandon the Dargai position at the end, they could claim satisfaction at their achievements if not outright victory. The British force had been held up, they had managed to escape with their own forces largely intact and they had carried away most of their own dead and wounded."I consider it unlikely that the Afghan defenders lost significantly more than the attack force, even with the effects of the artillery fire.

The Tirah Expedition continued on to the northeast the following day.

The Outcome: British tactical victory

The Impact: Minimal. The fiasco at Dargai didn't put a real dent in the Afghan resistance, and the British had other problems to worry about soon. As other military forces in the high hills around the Durand Line have discovered, it is usually the support elements that find it hard to cope with the Afghan and his mountains.

Constant and deadly harassment of supply and transport columns continued. Some of the more notable of these deadly little assaults included:

9 NOV 1897 Elements of the Northampton Regiment separated from supporting units and ambushed while burning some villages around Saran Sar. 20 killed, 48 wounded.

22 NOV 1897 One company Dorsets, one company Sikhs (unit unknown) ambushed while searching for troopers lost in contact. 29 killed, 44 wounded.

19 JAN 1898 36th Sikhs and the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) ambushed while patrolling out of Mamanai. 32 killed, 37 wounded; some of the badly wounded are left behind when the KOYLI retreats and are mutilated.

Now you notice the little item about what happened on 9 NOV?

"Burning villages"?

Yep.

The Brits didn't play that "hearts and minds" bullshit. The way they saw it, counterinsurgency was all about grabbing the insurgents by the balls and twisting those rascals until the rapscallions begged for mercy.

So the primary "job" of the soldiers in the Tirah Expedition, like pretty much every other "column" the British sent into the tribal areas, wasn't fighting tribesmen.

It was burning people's homes and crops. It was throwing stones into their wells to make them useless, it was lifting their cattle, sheep, and goats, it was doing just what the U.S. Army did to the Sioux, and the Cheyenne, the Seminoles, and the Creeks.

It was killing their men, and turning their women and children out in the wilderness to starve.

And it worked; it usually does. Eventually British logistical and numerical strength overwhelmed the tribesmen. In June 1898 negotiation resulted in a payment of 800 rifles and 50,000 rupees from the Afridi. The tribe also committed to dealing only with the Raj, and leaving road- and railway construction unmolested.

A new unit, the Khyber Rifles, was formed to replace the Afridi levies that had guarded the Khyber Pass. The troopers were Afridi but the officers were British, and there would be no more question of who were the Kings of the Khyber.

The British agreed to pay the tribal leaders stipends to keep the agreement, and the peace.

As you probably know, that peace has been most notable by its absence from that day to this.

But in the short term both sides seemed to get what they wanted.

Britain had a brisk little fight that ended in the restoration of British power over the hills around Dargai. The Northwest Frontier was secure for another several years from the threat of Afghan tribesmen working with the Russian Bear. British "honor" had been satisfied, and the truculent tribes "punished" for their fractious behavior. The troops has performed well, even if their leaders had made several critical blunders on the battlefield itself (such as at Dargai) and had, overall, failed to understand and adjust to the new tactical conditions they faced in the Orakzai hills.

The tribes also had reason to be pleased. Johnson (2009) notes that:

"They had inflicted considerable losses on the British and exchanged blow for blow in a manner that would accrue them honour and credit. Individuals who had survived the campaign would have been recognised as having demonstrated courage in defence of their lands, peoples and religion.The strange world in which Afghan and Briton alternated between fighting alongside and against each other continued for exactly another fifty years, until Independence in 1947.

The sense that the Pashtuns had actually enjoyed the campaign because it had offered them a chance to enhance their honour was confirmed by a bizarre epilogue to the Tirah Campaign. When General Lockhart set off to leave India in April 1898, a crowd of 500 Afridis including Zaka-Khels mobbed him with cheers and insisted on pulling his carriage to the station. Some vowed to fight alongside the British in the future and promised eternal friendship. To the Pashtuns, this campaign had not been a British victory, but a draw, and, more importantly, honour had been preserved for both sides."

The tribes of the high hills then passed into the portfolio of the new government of Pakistan, where they have remained a tumult and a shouting to this very day.

In Dorchester in the county of Dorset the monument to the dead men of Dargai goes largely unvisited and unremarked in the Borough Gardens, the names of the troopers killed on that chilly October day slowly fading from the stone.

The Gordon Highlanders ceased to be in 1994, forced into amalgamation with the other two remaining Highland regiments to form "the Highland Regiment". Currently the 4th Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland preserves what remains of the lineage and battle honors of the old 92nd Regiment of Foot; "Ninety-twa, no' deid yet".

On 8 NOV 2006 a suicide bomber - probably related to one of the Tarkani Pashtuns killed in an aerial attack on Bajaur nine days earlier - killed 42 Pakistani soldiers in the village of Dargai.